History Of The Puritans In North America on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In the early 17th century, thousands of

Two of the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth Colony -

Two of the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth Colony -

Once in New England, the Puritans established

Once in New England, the Puritans established

According to historian Bruce C. Daniels, the Puritans were " e of the most literate groups in the early modern world", with about 60 percent of New England able to read. At a time when the literacy rate in England was less than 30 percent, the Puritan leaders of colonial New England believed children should be educated for both religious and civil reasons, and they worked to achieve universal literacy. In 1642, Massachusetts required heads of households to teach their wives, children, and servants basic reading and writing so that they could read the Bible and understand colonial laws. In 1647, the government required all towns with 50 or more households to hire a teacher and towns of 100 or more households to hire a

According to historian Bruce C. Daniels, the Puritans were " e of the most literate groups in the early modern world", with about 60 percent of New England able to read. At a time when the literacy rate in England was less than 30 percent, the Puritan leaders of colonial New England believed children should be educated for both religious and civil reasons, and they worked to achieve universal literacy. In 1642, Massachusetts required heads of households to teach their wives, children, and servants basic reading and writing so that they could read the Bible and understand colonial laws. In 1647, the government required all towns with 50 or more households to hire a teacher and towns of 100 or more households to hire a

Slavery was legal in colonial New England; however, the slave population was less than three percent of the labor force. Most Puritan clergy accepted the existence of slavery since it was a practice recognized in the Bible (see

Slavery was legal in colonial New England; however, the slave population was less than three percent of the labor force. Most Puritan clergy accepted the existence of slavery since it was a practice recognized in the Bible (see

online

* * Manchester, Margaret Murányi. (2019). ''Puritan Family and Community in the English Atlantic World: Being "Much afflicted with conscience"'', Routledge. * * Morgan, Edmund S. (1958). ''The Puritan dilemma: The story of John Winthrop'

online

* Morgan, Edmund S. (1963). ''Visible saints : The history of a Puritan idea

online

* Morgan, Edmund S. (1966). ''The Puritan family : Religion & domestic relations in seventeenth-century New England'

online

* * * Stille, Darlene R. (2006). ''Anne Hutchinson: Puritan protester'' — for middle and secondary schools

online

* * * Winship, Michael P. (2018). ''Hot Protestants: A History of Puritanism in England and America'', Yale University Press — a major scholarly history

excertpt

* Zakai, Avihu. (2002). ''Exile and Kingdom: History and apocalypse in the Puritan migration to America'', Cambridge University Press.

online

online

{{refend History of Calvinism North American cultural history Puritanism in the United States

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

Puritans

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

colonized North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

, almost all in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. Puritans were intensely devout members of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

who believed that the Church of England was insufficiently reformed, retaining too much of its Roman Catholic doctrinal roots, and who therefore opposed royal ecclesiastical policy. Most Puritans were "non-separating Puritans" who did not advocate setting up separate congregations distinct from the Church of England; these were later called Nonconformists. A small minority of Puritans were "separating Puritans" who advocated setting up congregations outside the Church. The Pilgrims were a Separatist group, and they established the Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the British America, first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the pa ...

in 1620. Puritans went chiefly to New England, but small numbers went to other English colonies up and down the Atlantic.

Puritans played the leading roles in establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

in 1629, the Saybrook Colony

The Saybrook Colony was an English colony established in late 1635 at the mouth of the Connecticut River in present-day Old Saybrook, Connecticut by John Winthrop, the Younger, son of John Winthrop, the Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. ...

in 1635, the Connecticut Colony

The ''Connecticut Colony'' or ''Colony of Connecticut'', originally known as the Connecticut River Colony or simply the River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636 as a settl ...

in 1636, and the New Haven Colony

The New Haven Colony was a small English colony in North America from 1638 to 1664 primarily in parts of what is now the state of Connecticut, but also with outposts in modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

The history of ...

in 1638. The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was one of the original Thirteen Colonies established on the east coast of America, bordering the Atlantic Ocean. It was founded by Roger Williams. It was an English colony from 1636 until ...

was established by settlers expelled from Massachusetts because of their unorthodox religious opinions. Puritans were also active in New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

before it became a crown colony in 1691. Puritanism ended early in the 18th century and before 1740 was replaced by the much milder Congregational church.

Background (1533–1630)

Puritanism was aProtestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

movement that emerged in 16th-century England with the goal of transforming it into a godly society by reforming or purifying the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

of all remaining Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

teachings and practices. During the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

, Puritans were for the most part tolerated within the established church. Like Puritans, most English Protestants at the time were Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

in their theology, and many bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

s and Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

members were sympathetic to Puritan objectives. The major point of controversy between Puritans and church authorities was over liturgical

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

ceremonies Puritans thought too Catholic, such as wearing clerical vestments, kneeling to receive Holy Communion, and making the sign of the cross

Making the sign of the cross ( la, signum crucis), or blessing oneself or crossing oneself, is a ritual blessing made by members of some branches of Christianity. This blessing is made by the tracing of an upright cross or + across the body with ...

during baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost ...

.

During the reign of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, most Puritans were no longer willing to wait for further church reforms and separated from the Church of England. Since the law required everyone to attend parish services, these Separatists were vulnerable to criminal prosecution and some such as Henry Barrow

Henry Barrow (or Barrowe) ( – 6 April 1593) was an English Separatist Puritan, or Brownist, executed for his views. He led the London Underground Church from 1587 to 1593, spending most of that time in prison, and wrote numerous works of Br ...

and John Greenwood John Greenwood may refer to:

Sportspeople

* John Greenwood (cricketer, born 1851) (1851–1935), English cricketer

* John Eric Greenwood (1891–1975), rugby union international who represented England

* John Greenwood (footballer) (1921–1994) ...

were executed. To escape persecution and worship freely, some Separatists migrated to the Netherlands. Nevertheless, most Puritans remained within the Church of England.

Under Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, Calvinist teachings were undermined and bishops became less tolerant of Puritan views and more willing to enforce the use of controversial ceremonies. New controls were placed on Puritan preaching, and some ministers were suspended or removed from their livings. Increasingly, many Puritans concluded that they had no choice but to emigrate.

Migration to America (1620–1640)

In 1620, a group of Separatists known as the Pilgrims settled inNew England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

and established the Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes Plimouth) was, from 1620 to 1691, the British America, first permanent English colony in New England and the second permanent English colony in North America, after the Jamestown Colony. It was first settled by the pa ...

. The Pilgrims originated as a dissenting

Dissent is an opinion, philosophy or sentiment of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or policy enforced under the authority of a government, political party or other entity or individual. A dissenting person may be referred to as ...

congregation in Scrooby

Scrooby is a small village on the River Ryton in north Nottinghamshire, England, near Bawtry in South Yorkshire. At the time of the 2001 census it had a population of 329. Until 1766, it was on the Great North Road so became a stopping-off po ...

led by Richard Clyfton

Richard Clyfton (Clifton) (died 1616) was an English Brownist minister, at Scrooby, Nottinghamshire, and then in Amsterdam.

Life

He is identified with the Richard Clifton who, on 12 February 1585, was instituted to the vicarage of Marnham, nea ...

, John Robinson and William Brewster. This congregation was subject to persecution with members being imprisoned or having property seized. Fearing greater persecution, the group left England and settled in the Dutch city of Leiden. In 1620, after receiving a patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

from the London Company, the Pilgrims left for New England on board the ''Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

'', landing at Plymouth Rock

Plymouth Rock is the traditional site of disembarkation of William Bradford and the ''Mayflower'' Pilgrims who founded Plymouth Colony in December 1620. The Pilgrims did not refer to Plymouth Rock in any of their writings; the first known writt ...

. The Pilgrims are remembered for creating the Mayflower Compact, a social contract

In moral and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships betw ...

based on Puritan political theory and in imitation of the church covenant

A church covenant is a declaration, which some churches draw up and call their members to sign, in which their duties as church members towards God and their fellow believers are outlined. It is a fraternal agreement, freely endorsed, that establi ...

they had made in Scrooby.

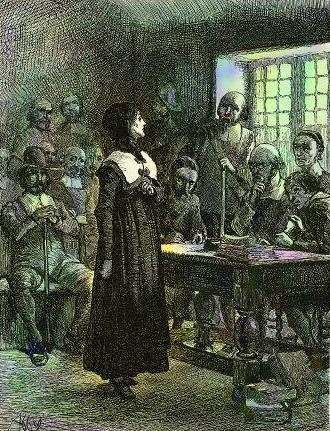

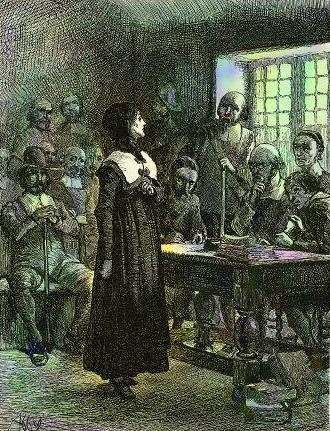

Two of the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth Colony -

Two of the Pilgrim settlers in Plymouth Colony - Robert Cushman

Robert Cushman (1577–1625) was an important leader and organiser of the ''Mayflower'' voyage in 1620, serving as Chief Agent in London for the Leiden Separatist contingent from 1617 to 1620 and later for Plymouth Colony until his death in 1625 ...

and Edward Winslow

Edward Winslow (18 October 15958 May 1655) was a Separatist and New England political leader who traveled on the ''Mayflower'' in 1620. He was one of several senior leaders on the ship and also later at Plymouth Colony. Both Edward Winslow and ...

- believed that Cape Ann

Cape Ann is a rocky peninsula in northeastern Massachusetts, United States on the Atlantic Ocean. It is about northeast of Boston and marks the northern limit of Massachusetts Bay. Cape Ann includes the city of Gloucester and the towns of ...

would be a profitable location for a settlement. They, therefore, organized a company named the Dorchester Company and in 1622 sailed to England seeking a patent from the London Company giving them permission to settle there. They were successful and were granted the Sheffield Patent (named after Edmund, Lord Sheffield, the member of the Plymouth Company who granted the patent). On the basis of this patent, Roger Conant led a group of fishermen from the area later called Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

to found Salem in 1626, being replaced as governor by John Endecott

John Endecott (also spelled Endicott; before 1600 – 15 March 1664/1665), regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He serv ...

in 1628 or 1629.

Other Puritans were convinced that New England could provide a religious refuge, and the enterprise was reorganized as the Massachusetts Bay Company. In March 1629, it succeeded in obtaining from King Charles a royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, bu ...

for the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

. In 1630, the first ships of the Great Puritan Migration sailed to the New World, led by John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

.

During the crossing, Winthrop preached a sermon entitled "A Model of Christian Charity

"A Model of Christian Charity" is a sermon by Puritan leader John Winthrop, preached at the Holyrood Church in Southampton before the colonists embarked in the Winthrop Fleet. It is also known as " City upon a Hill" and denotes the notion of Ameri ...

", in which he told his followers that they had entered a covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

with God according to which he would cause them to prosper if they maintained their commitment to God. In doing so, their new colony would become a " City upon a Hill", meaning that they would be a model to all the nations of Europe as to what a properly reformed Christian commonwealth should look like.

Most of the Puritans who emigrated settled in the New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

area. However, the Great Migration of Puritans was relatively short-lived and very large. It began in earnest in 1629 with the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

, and ended in 1642 with the start of the English Civil War when King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

effectively shut off emigration to the colonies. Emigration was officially restricted to conforming churchmen in December 1634 by his Privy Council. From 1629 through 1643, approximately 21,000 Puritans immigrated to New England.

The Great Migration of Puritans to New England was primarily an exodus of families. Between 1630 and 1640, over 13,000 men, women, and children sailed to Massachusetts. The religious and political factors behind the Great Migration influenced the demographics

Demography () is the statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups defined by criteria such as ed ...

of the emigrants. Groups of young men seeking economic success predominated the Virginia colonies, whereas Puritan ships were laden with "ordinary" people, old and young, families as well as individuals. Just a quarter of the emigrants were in their twenties when they boarded ships in the 1630s, making young adults a minority in New England settlements. The New World Puritan population was more of a cross-section in the age of the English population than those of other colonies. This meant that the Massachusetts Bay Colony retained a relatively normal population composition. In the colony of Virginia, the ratio of colonist men to women was 4:1 in the early decades and at least 2:1 in later decades, and only limited intermarriage took place with Native women. By contrast, nearly half of the Puritan immigrants to the New World were women, and there was very little intermarriage with Native Americans. The majority of families who traveled to Massachusetts Bay were families in progress, with parents who were not yet through with their reproductive years and whose continued fertility made New England's population growth possible. The women who emigrated were critical agents in the success of the establishment and maintenance of the Puritan colonies in North America. Success in the early colonial economy depended largely on labor, which was conducted by members of Puritan families.Other destinations

The struggle between the assertive Church of England and various Presbyterian and Puritan groups extended throughout the English realm in the 17th Century, prompting not only the -emigration of British Presbyterians from Ireland to North America (the '' Scotch-Irish''), but prompting emigration fromBermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

, England's second-oldest overseas territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

. Roughly 10,000 Bermudians emigrated before 1775. Most of these went to the American colonies, founding, or contributing to settlements throughout the South, especially. Many went to the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, where a number of Bermudian Independent Puritan families, under the leadership of William Sayle

Captain William Sayle (c. 1590–1671) was a prominent British landholder who was Governor of Bermuda in 1643 and again in 1658. As an Independent in religion and politics, and an adherent of Oliver Cromwell, he was dissatisfied with life in Ber ...

, had established the colony of Eleuthera

Eleuthera () refers both to a single island in the archipelagic state of The Commonwealth of the Bahamas and to its associated group of smaller islands. Eleuthera forms a part of the Great Bahama Bank. The island of Eleuthera incorporates the ...

in 1648.

Emigration resumed under the rule of Cromwell in the 1650s, but not in large numbers as there was no longer any need to escape persecution in England. Some Puritans returned to England during the English Civil War. They were on the winning side and remained under Oliver Cromwell's Puritanical rule.

Life in the New World

Puritan dominance in the New World lasted until the early 1700s. That era can be broken down into three parts: the generation of John Cotton andRichard Mather

Richard Mather (1596 – 22 April 1669) was a New England Puritan minister in colonial Boston. He was father to Increase Mather and grandfather to Cotton Mather, both celebrated Boston theologians.

Biography

Mather was born in Lowton in the p ...

, 1630–62 from the founding to the Restoration, years of virtual independence and nearly autonomous development; the generation of Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the administ ...

, 1662–89 from the Restoration and the Halfway Covenant to the Glorious Revolution, years of struggle with the British crown; and the generation of Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a New England Puritan clergyman and a prolific writer. Educated at Harvard College, in 1685 he joined his father Increase as minister of the Congregationalist Old North Meeting H ...

, 1689–1728 from the overthrow of Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

(in which Cotton Mather played a part) and the new charter, mediated by Increase Mather, to the death of Cotton Mather.

Religion

Once in New England, the Puritans established

Once in New England, the Puritans established Congregational churches

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs it ...

that subscribed to Reformed theology

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Calv ...

. The Savoy Declaration

The Savoy Declaration is a Congregationalist confession of Faith. Its full title is ''A Declaration of the Faith and Order owned and practised in the Congregational Churches in England.'' It was drawn up in October 1658 by English Independents a ...

, a modification of the Westminster Confession of Faith

The Westminster Confession of Faith is a Reformed confession of faith. Drawn up by the 1646 Westminster Assembly as part of the Westminster Standards to be a confession of the Church of England, it became and remains the "subordinate standard" ...

, was adopted as a confessional statement by the churches in Massachusetts in 1680 and the churches of Connecticut in 1708.

The Cambridge Platform describes Congregationalist polity as practiced by Puritans in the 17th century. Every congregation was founded upon a church covenant

A church covenant is a declaration, which some churches draw up and call their members to sign, in which their duties as church members towards God and their fellow believers are outlined. It is a fraternal agreement, freely endorsed, that establi ...

, a written agreement signed by all members in which they agreed to uphold congregational principles, to be guided by ''sola scriptura

, meaning by scripture alone, is a Christian theological doctrine held by most Protestant Christian denominations, in particular the Lutheran and Reformed traditions of Protestantism, that posits the Bible as the sole infallible source of aut ...

'' in their decision making, and to submit to church discipline

Church discipline is the practice of church members calling upon an individual within the Church to repent for their sins. Church discipline is performed when one has sinned or gone against the rules of the church. Church discipline is practiced wi ...

. The right of each congregation to elect its own officers and manage its own affairs was upheld.

For church offices, Puritans imitated the model developed in Calvinist Geneva. There were two major offices: elder (or presbyter) and deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Churc ...

. Initially, there were two types of elders. Ministers

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of governme ...

, whose responsibilities included preaching and administering the sacraments, were referred to as teaching elders. Large churches would have two ministers, one to serve as pastor

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and ...

and the other to serve as teacher. Prominent laymen would be elected for life as ruling elders. Ruling elders governed the church alongside teaching elders, and, while they could not administer the sacraments, they could preach. In the beginning, deacons largely handled financial matters. By the middle of the 17th century, most churches no longer had lay elders, and deacons assisted the minister in leading the church. Other than elders and deacons, congregations also elected messengers to represent them in synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''wikt:synod, synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin ...

s (church councils) for the purpose of offering non-binding advisory opinions.

The essential Puritan belief was that people are saved by grace alone

''Sola gratia'', meaning by grace alone, is one of the five ''solae'' and consists in the belief that salvation comes by divine grace or "unmerited favor" only, not as something earned or deserved by the sinner. It is a Christian theologica ...

and not by any merit

Merit may refer to:

Religion

* Merit (Christianity)

* Merit (Buddhism)

* Punya (Hinduism)

* Imputed righteousness in Reformed Christianity

Companies and brands

* Merit (cigarette), a brand of cigarettes made by Altria

* Merit Energy Company, ...

from doing good works

In Christian theology, good works, or simply works, are a person's (exterior) actions or deeds, in contrast to inner qualities such as grace or faith.

Views by denomination

Anglican Churches

The Anglican theological tradition, including The ...

. At the same time, Puritans also believed that men and women "could labor to make themselves ''appropriate'' vessels of saving grace" mphasis in original They could accomplish this through Bible reading, prayer, and doing good works. This doctrine was called preparationism Preparationism is the view in Christian theology that unregenerate people can take steps in preparation for conversion, and should be exhorted to do so. Preparationism advocates a series of things that people need to do before they come to belie ...

, and nearly all Puritans were preparationists to some extent. The process of conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

was described in different ways, but most ministers agreed that there were three essential stages. The first stage was humiliation or sorrow for having sinned against God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

. The second stage was justification or adoption

Adoption is a process whereby a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person's biological or legal parent or parents. Legal adoptions permanently transfer all rights and responsibilities, along with filiation, from ...

characterized by a sense of having been forgiven and accepted by God through Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

's mercy. The third stage was sanctification, the ability to live a holy life out of gladness toward God.

Puritans believed churches should be composed of "visible saints" or the elect

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

. To ensure that only regenerated persons were admitted as full members, New England churches required prospective members to provide a conversion narrative Broadly speaking, a conversion narrative is a narrative that relates the operation of conversion, usually religious. As a specific aspect of American literary and religious history, the conversion narrative was an important facet of Puritan sacred a ...

describing their personal conversion experience. All settlers were required to attend church services and were subject to church discipline

Church discipline is the practice of church members calling upon an individual within the Church to repent for their sins. Church discipline is performed when one has sinned or gone against the rules of the church. Church discipline is practiced wi ...

. The Lord's Supper, however, was reserved to full members only. Puritans practiced infant baptism

Infant baptism is the practice of baptising infants or young children. Infant baptism is also called christening by some faith traditions.

Most Christians belong to denominations that practice infant baptism. Branches of Christianity that ...

, but only church members in full communion could present their children for baptism. Members' children were considered part of the church and covenant by birth and were entitled to baptism. Nevertheless, these children would not enjoy the full privileges of church membership until they provided a public account of conversion.

Church services were held in the morning and afternoon on Sunday, and there was usually a mid-week service. The ruling elders and deacons sat facing the congregation on a raised seat. Men and women sat on opposite sides of the meeting house, and children sat in their own section under the oversight of a tithing

A tithing or tything was a historic English legal, administrative or territorial unit, originally ten hides (and hence, one tenth of a hundred). Tithings later came to be seen as subdivisions of a manor or civil parish. The tithing's leader or s ...

man, who corrected unruly children (or sleeping adults) with a long staff. The pastor opened the service with prayer for about 15 minutes, the teacher then read and explained the selected Bible passage, and a ruling elder then led in singing a Psalm

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

, usually from the Bay Psalm Book

''The Whole Booke of Psalmes Faithfully Translated into English Metre'', commonly called the Bay Psalm Book, is a metrical psalter first printed in 1640 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was the first book printed in British North America. The ...

. The pastor then preached for an hour or more, and the teacher ended the service with prayer and benediction. In churches with only one minister, the morning sermon was devoted to the argument (interpreting the biblical text and justifying that interpretation) and the afternoon sermon to its application (the lessons that could be drawn from the text for the individual or for the collective community).

Church and state

For Puritans, the people of society were bound together by a social covenant (such as Plymouth's Mayflower Compact, Connecticut'sFundamental Orders

The Fundamental Orders were adopted by the Connecticut Colony council on . The fundamental orders describe the government set up by the Connecticut River New England town, towns, setting its structure and powers. They wanted the government to hav ...

, New Haven's Fundamental Agreement, and Massachusetts' colonial charter). Having entered into such a covenant, eligible voters were responsible for choosing qualified men to govern and to obey such rulers, who ultimately received their authority from God and were responsible for using it to promote the common good. If the ruler was evil, however, the people were justified in opposing and rebelling against him. Such notions helped New Englanders justify the English Puritan Revolution

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians ("Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of reli ...

of the 1640s, the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

of 1688, and the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

of 1775.

The Puritans also believed they were in a national covenant with God. They believed they were chosen by God to help redeem the world by their total obedience to his will. If they were true to the covenant, they would be blessed; if not, they would fail. Within this worldview, it was the government's responsibility to enforce moral standards and ensure true religious worship was established and maintained. In the Puritan colonies, the Congregational church functioned as a state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

. In Massachusetts, no new church could be established without the permission of the colony's existing Congregational churches and the government. Likewise, Connecticut allowed only one church per town or parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

, which had to be Congregational.

All residents in Massachusetts and Connecticut were required to pay taxes for the support of the Congregational churches, even if they were religious dissenters. The franchise was limited to Congregational church members in Massachusetts and New Haven, but voting rights were more extensive in Connecticut and Plymouth. In Connecticut, church attendance on Sundays was mandatory (for both church members and non-members), and those who failed to attend were fined.

There was a greater separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

in the Puritan commonwealths than existed anywhere in Europe at the time. In England, the king was head of both church and state, bishops sat in Parliament and the Privy Council, and church officials exercised many secular functions. In New England, secular matters were handled only by civil authorities, and those who held offices in the church were barred from holding positions in the civil government. When dealing with unorthodox persons, Puritans believed that the church, as a spiritual organization, was limited to "attempting to persuade the individual of his error, to warn him of the dangers he faced if he publicly persisted in it, and—as a last resort—to expel him from the spiritual society by ex-communication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

." Citizens who lost church membership by ex-communication retained the right to vote in civil affairs.

Religious toleration

The Puritans did not come to America to establish atheocracy

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deity, deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy origina ...

, but neither did they institute religious freedom

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedom ...

. Puritans believed that the state was obligated to protect society from heresy, and it was empowered to use corporal punishment, banishment, and execution. New England magistrates did not investigate private views, but they did take action against public dissent from the religious establishment. Puritan sentiments were expressed by Nathaniel Ward

Nathaniel Ward (1578 – October 1652) was a Puritan clergyman and pamphleteer in England and Massachusetts.

Biography

A son of John Ward, a noted Puritan minister, he was born in Haverhill, Suffolk, England. He studied law and graduated fr ...

in ''The Simple Cobbler of Agawam'': "all Familists, Antinomians, Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

, and other Enthusiasts

In modern usage, enthusiasm refers to intense enjoyment, interest, or approval expressed by a person. The term is related to playfulness, inventiveness, optimism and high energy. The word was originally used to refer to a person possessed by G ...

shall have free Liberty to keep away from us, and such as will come hall have liberty

In architecture, a hall is a relatively large space enclosed by a roof and walls. In the Iron Age and early Middle Ages in northern Europe, a mead hall was where a lord and his retainers ate and also slept. Later in the Middle Ages, the grea ...

to be gone as fast as they can, the sooner the better."

The period 1658–1692 saw the execution of Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

(see Boston martyrs

The Boston martyrs is the name given in Quaker tradition to the three English members of the Society of Friends, Marmaduke Stephenson, William Robinson and Mary Dyer, and to the Barbadian Friend William Leddra, who were condemned to death and e ...

) and the imprisonment of Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

. Quakers were initially banished by colonial courts, but they often returned in defiance of authorities. Historian Daniel Boorstin

Daniel Joseph Boorstin (October 1, 1914 – February 28, 2004) was an American historian at the University of Chicago who wrote on many topics in American and world history. He was appointed the twelfth Librarian of the United States Congress in ...

stated, "the Puritans had not sought out the Quakers in order to punish them; the Quakers had come in quest of punishment."

Family life

For Puritans, the family was the "locus of spiritual and civic development and protection", and marriage was the foundation of the family and, therefore, society. Unlike in England, where people were married by ministers in the church according to the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'', Puritans saw no biblical justification for church weddings or the exchange of wedding rings. While marriage held great religious significance for Puritans—they saw it as a covenant relationship freely entered into by both man and wife—the wedding was viewed as a private, contractual event officiated by a civil magistrate either in the home of the magistrate or a member of the bridal party. Massachusetts ministers were not legally permitted to solemnize marriages until 1686 after the colony had been placed under royal control, but by 1726 it had become the accepted tradition.

According to scholars Gerald Moran and Maris Vinovskis, some historians argue that Puritan child-rearing was repressive. Central to this argument is the views of John Robinson, the Pilgrims' first pastor, who wrote in a 1625 treatise "Of Children and Their Education", "And surely there is in all children, though not alike, a stubbornness, and stoutness of mind arising from natural pride, which must, in the first place, be broken and beaten down." Moran and Vinovskis, however, argue that Robinson's views were not representative of 17th-century Puritans. They write that Puritan parents "exercised an authoritative, not an authoritarian, mode of child-rearing" that aimed to cultivate godly affections and reason, with corporal punishment used as a last resort.

Education

According to historian Bruce C. Daniels, the Puritans were " e of the most literate groups in the early modern world", with about 60 percent of New England able to read. At a time when the literacy rate in England was less than 30 percent, the Puritan leaders of colonial New England believed children should be educated for both religious and civil reasons, and they worked to achieve universal literacy. In 1642, Massachusetts required heads of households to teach their wives, children, and servants basic reading and writing so that they could read the Bible and understand colonial laws. In 1647, the government required all towns with 50 or more households to hire a teacher and towns of 100 or more households to hire a

According to historian Bruce C. Daniels, the Puritans were " e of the most literate groups in the early modern world", with about 60 percent of New England able to read. At a time when the literacy rate in England was less than 30 percent, the Puritan leaders of colonial New England believed children should be educated for both religious and civil reasons, and they worked to achieve universal literacy. In 1642, Massachusetts required heads of households to teach their wives, children, and servants basic reading and writing so that they could read the Bible and understand colonial laws. In 1647, the government required all towns with 50 or more households to hire a teacher and towns of 100 or more households to hire a grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

instructor to prepare promising boys for college. Boys interested in the ministry were often sent to colleges such as Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

(founded in 1636) or Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

(founded in 1707).

The Puritans anticipated the educational theories of John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

and other Enlightenment thinkers. Like Locke's blank slate

''Tabula rasa'' (; "blank slate") is the theory that individuals are born without built-in mental content, and therefore all knowledge comes from experience or perception. Epistemological proponents of ''tabula rasa'' disagree with the doctri ...

, Puritans believed that a child's mind was "an empty receptacle, one that had to be infused with the knowledge gained from careful instruction and education."

The Puritans in the United States were great believers in education. They wanted their children to be able to read the Bible themselves, and interpret it themselves, rather than have to have a clergyman tell them what it says and means. This then leads to thinking for themselves, which is the basis of democracy.

The Puritans, almost immediately after arriving in America in 1630, set up schools for their sons. They also set up what were called dame schools for their daughters, and in other cases taught their daughters at home how to read. As a result, Americans were the most literate people in the world. By the time of the American Revolution, there were 40 newspapers in the United States (at a time when there were only two cities – New York and Philadelphia – with as many as 20,000 people in them).

The Puritans also set up a college (Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

) only six years after arriving in the United States. By the time of the Revolution, the United States had 10 colleges (when England had only two).

Recreation and leisure

Puritans did not celebrate traditional holidays such as Christmas, Easter, or May Day. They also did not observe personal annual holidays, such as birthdays or anniversaries. They did, however, celebrate special occasions such as military victories, harvests,ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorization, authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominational ...

s, weddings, and births. These celebrations consisted of food and conversation. Beyond special occasions, the tavern was an important place for people to gather for fellowship on a regular basis.

Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and president of Harvard College for twenty years (1681–1701). He was influential in the administ ...

wrote that dancing was "a natural expression of joy; so that there is no more sin in it than in laughter." Puritans generally discouraged mixed or "promiscuous" dancing between men and women, which according to Mather would lead to "unchaste touches and gesticulations. .. hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

have a palpable tendency to that which is evil." Some ministers, including John Cotton, thought that mixed dancing was appropriate under special circumstances, but all agreed it was a practice not to be encouraged. Dancing was also discouraged at weddings or on holidays (especially dancing around the Maypole) and was illegal in taverns.

Puritans had no theological objections to sports and games as long as they did not involve gambling (which eliminated activities such as billiards, shuffleboard, horse racing, bowling, and cards). They also opposed blood sports

A blood sport or bloodsport is a category of sport or entertainment that involves bloodshed. Common examples of the former include combat sports such as cockfighting and dog fighting, and some forms of hunting and fishing. Activities charact ...

, such as cockfighting, cudgel-fighting, and bear-baiting. Team sports, such as football, were problematic because "they encouraged idleness, produced injuries, and created bitter rivalries." Hunting and fishing were approved because they were productive. Other sports were encouraged for promoting civic virtue, such as competitions of marksmanship, running, and wrestling held within militia companies.

Only a few activities were completely condemned by Puritans. They were most opposed to the theater. According to historian Bruce Daniels, plays were seen as "false recreations because they exhausted rather than relaxed the audience and actors" and also "wasted labor, led to wantonness and homosexuality, and invariably were represented by Puritans as a foreign—particularly French or Italian—disease of a similar enervating nature as syphilis." All forms of gambling were illegal. Not only were card-playing, dice throwing and other forms of gambling seen as contrary to the values of "family, work, and honesty", they were religiously offensive because gamblers implicitly asked God to intervene in trivial matters, violating the Third Commandment against taking the Lord's name in vain.

Slavery

Slavery was legal in colonial New England; however, the slave population was less than three percent of the labor force. Most Puritan clergy accepted the existence of slavery since it was a practice recognized in the Bible (see

Slavery was legal in colonial New England; however, the slave population was less than three percent of the labor force. Most Puritan clergy accepted the existence of slavery since it was a practice recognized in the Bible (see The Bible and Slavery

The Bible contains many references to slavery, which was a common practice in antiquity. Biblical texts outline sources and the legal status of slaves, economic roles of slavery, types of slavery, and debt slavery, which thoroughly explain t ...

). They also acknowledged that all people—whether white, black or Native American—were persons with souls who might receive saving grace. For this reason, slaves and free black people were eligible for full church membership; though, meetinghouses and burial grounds were racially segregated. The Puritan influence over society meant that slaves were treated better in New England than in the Southern colonies. In Massachusetts, the law gave slaves "all the liberties and Christian usages which the law of God established in Israel doth morally require". As a result, slaves received the same protections against mistreatment as white servants. Slave marriages were legally recognized, and slaves were also entitled to a trial by jury, even if accused of a crime by their master.

In 1700, Massachusetts judge and Puritan Samuel Sewall

Samuel Sewall (; March 28, 1652 – January 1, 1730) was a judge, businessman, and printer in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, best known for his involvement in the Salem witch trials, for which he later apologized, and his essay ''The Selling ...

published ''The Selling of Joseph'', the first antislavery tract written in America. In it, Sewall condemned slavery and the slave trade and refuted many of the era's typical justifications for slavery.

In the decades leading up to the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

such as Theodore Parker

Theodore Parker (August 24, 1810 – May 10, 1860) was an American transcendentalist and reforming minister of the Unitarian church. A reformer and abolitionist, his words and popular quotations would later inspire speeches by Abraham Lincol ...

, Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

, Henry David Thoreau and Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

repeatedly used the Puritan heritage of the country to bolster their cause. The most radical anti-slavery newspaper, '' The Liberator'', invoked the Puritans and Puritan values over a thousand times. Parker, in urging New England Congressmen to support the abolition of slavery, wrote that "The son of the Puritan ... is sent to Congress to stand up for Truth and Right ..."Commager, Henry Steele. ''Theodore Parker,'' pp. 206, 208-9, 210, The Beacon Press, Boston, Massachusetts, 1947.

Controversies

Roger Williams

Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

, a Separating Puritan minister, arrived in Boston in 1631. He was immediately invited to become the teacher at the Boston church, but he refused the invitation on the grounds that the congregation had not separated from the Church of England. He then was invited to become the teacher of the church at Salem but was blocked by Boston political leaders, who objected to his separatism. He thus spent two years with his fellow Separatists in the Plymouth Colony but ultimately came into conflict with them and returned to Salem, where he became the unofficial assistant pastor to Samuel Skelton.

Williams held many controversial views that irritated the colony's political and religious leaders. He criticized the Puritan clergy's practice of meeting regularly for consultation, seeing in this a drift toward Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

. William's concern for the purity of the church led him to oppose the mixing of the elect and the unregenerate for worship and prayer, even when the unregenerate were family members of the elect. He also believed that Massachusetts rightfully belonged to the Native Americans and that the king had no authority to give it to the Puritans. Because he feared that government interference in religion would corrupt the church, Williams rejected the government's authority to punish violations of the first four Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ� ...

and believed that magistrates should not tender an oath

An, AN, aN, or an may refer to:

Businesses and organizations

* Airlinair (IATA airline code AN)

* Alleanza Nazionale, a former political party in Italy

* AnimeNEXT, an annual anime convention located in New Jersey

* Anime North, a Canadian an ...

s to unconverted persons, which would have effectively abolished civil oaths.

In 1634, Skelton died, and the Salem congregation called Williams to be its pastor. In July 1635, however, he was brought before the General Court to answer for his views on oaths. Williams refused to back down, and the General Court warned Salem not to install him in any official position. In response, Williams decided that he could not maintain communion with the other churches in the colony nor with the Salem church unless they joined him in severing ties with the other churches. Caught between Williams and the General Court, the Salem congregation rejected Williams's extreme views.

In October, Williams was once again called before the General Court and refused to change his opinions. Williams was ordered to leave the colony and given until spring to do so, provided he ceased spreading his views. Unwilling to do so, the government issued orders for his immediate return to England in January 1636, but John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

warned Williams, allowing him to escape. In 1636, the exiled Williams founded the colony of Providence Plantation. He was one of the first Puritans to advocate separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular sta ...

, and Providence Plantation was one of the first places in the Christian world to recognize freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedom ...

.

Antinomian Controversy

Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (née Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her ...

and her family moved from Boston, Lincolnshire

Boston is a market town and inland port in the borough of the same name in the county of Lincolnshire, England. Boston is north of London, north-east of Peterborough, east of Nottingham, south-east of Lincoln, south-southeast of Hul ...

, to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634, following their Puritan minister John Cotton. Cotton became the teacher of the Boston church, working alongside its pastor John Wilson, and Hutchinson joined the congregation. In 1635, Hutchinson began holding meetings in her home to summarize the previous week's sermons for women who had been absent. Such gatherings were not unusual.

In October 1635, Wilson returned from a trip to England, and his preaching began to concern Hutchinson. Like most of the clergy in Massachusetts, Wilson taught preparationism Preparationism is the view in Christian theology that unregenerate people can take steps in preparation for conversion, and should be exhorted to do so. Preparationism advocates a series of things that people need to do before they come to belie ...

, the belief that human actions were "a means of preparation for God’s grant of saving grace and ... evidence of sanctification." Cotton's preaching, however, emphasized the inevitability of God's will rather than human preparatory action. These two positions were a matter of emphases, as neither Cotton nor Wilson believed that good works could save a person. For Hutchinson, however, the difference was significant, and she began to criticize Wilson in her private meetings.

In the summer of 1636, Hutchinson's meetings were attracting powerful men such as William Aspinwall

William Aspinwall (1605 – c. 1662) was an Englishman who emigrated to Boston with the ''Winthrop Fleet'' in 1630. He played an integral part in the early religious controversies of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Life

Aspinwall as most of t ...

, William Coddington

William Coddington (c. 1601 – 1 November 1678) was an early magistrate of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and later of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He served as the judge of Portsmouth and Newport, governor of Portsmouth ...

, John Coggeshall

John Coggeshall Sr. (2 December 1599 – 27 November 1647) was one of the founders of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations and the first President of all four towns in the Colony. He was a successful silk merchant in Essex, Eng ...

, and the colony's governor, Henry Vane. The group's credibility was increased due to the perceived support of Cotton and the definite support of Hutchinson's brother-in-law, the minister John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hamp ...

. By this time, Hutchinson was criticizing all the ministers in the colony, with the exception of Cotton and Wheelwright, for teaching legalism and preaching a "covenant of works" rather than a "covenant of grace". While denouncing the Puritan clergy as Arminians

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the ''Rem ...

, Hutchinson maintained "that assurance of salvation was conveyed not by action but by an essentially mystical experience of grace—an inward conviction of the coming of the Spirit to the individual that bore no relationship to moral conduct." By rejecting adherence to the moral law, Hutchinson was teaching Antinomianism

Antinomianism (Ancient Greek: ἀντί 'anti''"against" and νόμος 'nomos''"law") is any view which rejects laws or legalism and argues against moral, religious or social norms (Latin: mores), or is at least considered to do so. The term ha ...

, according to her clerical opponents.

Tensions continued to increase in the Boston church between Wilson and Hutchinson's followers, who formed a majority of the members. In January 1637, they were nearly successful in censuring

A censure is an expression of strong disapproval or harsh criticism. In parliamentary procedure, it is a debatable main motion that could be adopted by a majority vote. Among the forms that it can take are a stern rebuke by a legislature, a spir ...

him, and in the months that followed, they left the meeting house whenever Wilson began to preach. The General Court ordered a day of fasting and prayer to help calm tensions, but Wheelwright preached a sermon on that day that further inflamed tensions, for which he was found guilty of sedition. Because Governor Vane was one of Hutchinson's followers, the general election of 1637 became a battlefront in the controversy, and Winthrop was elected to replace Vane.

A synod of New England clergy was held in August 1637. The ministers defined 82 errors attributed to Hutchinson and her followers. It also discouraged private religious meetings and criticizing the clergy. In November, Wheelwright was banished from the colony. Hutchinson herself was called before the General Court where she ably defended herself. Nevertheless, she was ultimately convicted and sentenced to banishment from the colony due in part to her claims of receiving direct personal revelations from God. Other supporters were disenfranchised or forbidden from bearing arms unless they admitted their errors. Hutchinson received a church trial in March 1638 in which the Boston congregation switched sides and unanimously voted for Hutchinson's ex-communication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

. This effectively ended the controversy.

While often described as a struggle for religious liberty, historian Francis Bremer states that this is a misunderstanding. Bremer writes, "Anne Hutchinson was every bit as intolerant as her enemies. The struggle was over which of two competing views would be crowned and enforced as New England orthodoxy. As a consequence of the crisis she precipitated, the range of views that were tolerated in the Bay actually narrowed."

In the aftermath of the crisis, ministers realized the need for greater communication between churches and the standardization of preaching. As a consequence, nonbinding ministerial conferences to discuss theological questions and address conflicts became more frequent in the following years. A more substantial innovation was the implementation of the "third way of communion", a method of isolating a dissident or heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

church from neighboring churches. Members of an offending church would be unable to worship or receive the Lord's Supper

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

in other churches.

Historiography of Puritan Involvement with Witchcraft in Colonial America

As time passes and different perspectives arise within the scholarship of witchcraft and its involvement in Puritan New England, many scholars have stepped forth to contribute to what we know in regards to this subject. For instance, diverse perspectives involving the witch trials have been argued involving gender, race, economics, religion, and the social oppression that Puritans lived through that explain in a more in-depth way how Puritanism contributed to the trials and executions. Puritan fears, beliefs, and institutions were the perfect storm that fueled the witch craze in towns such as Salem from an interdisciplinary and anthropological approach. From a gendered approach, offered by Carol Karlsen and Elizabeth Reis, the question of why witches were primarily women did not fully surface until after the second wave of feminism in the 1980s. Some believe that women who were gaining economic or social power, specifically in the form of land inheritance, were at a higher risk of being tried as witches. Others maintain that females were more susceptible to being witches as the Puritans believed that the weak body was a pathway to the soul which both God and the Devil fought for. Due to the Puritan belief that female bodies "lacked the strength and vitality" compared to male bodies, females were more susceptible to make a choice to enter a covenant with Satan as their fragile bodies could not protect their souls. From a racial perspective, Puritans believed that African Americans and Native Americans living within the colonies were viewed as "true witches" from an anthropological sense as Blacks were considered "inherently evil creatures, unable to control their connection to Satanic wickedness." Another contribution made to scholarship includes the religious perspective that historians attempt to understand its effect on the witch trials. J.P. Demos, a major scholar in the field of Puritan witchcraft studies, maintains that the intense and oppressive nature of Puritan religion can be viewed as the main culprit in the Colonial witch trials. While many scholars provide different arguments to Puritanism and witchcraft, all of the various camps mentioned rely on each other in numerous ways in order to build on our understanding of the witch craze in early American History. As more perspectives from different scholars add to the knowledge of the Puritan involvement in the witch trials, a more complete picture and history will form.Decline of power and influence

The decline of the Puritans and the Congregational churches was brought about first through practices such as theHalf-Way Covenant

The Half-Way Covenant was a form of partial church membership adopted by the Congregational churches of colonial New England in the 1660s. The Puritan-controlled Congregational churches required evidence of a personal conversion experience befo ...

and second through the rise of dissenting Baptists, Quakers, Anglicans and Presbyterians in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

There is no consensus on when the Puritan era ended, though it is agreed that it was over by 1740. By this time, the Puritan tradition was splintering into different strands of pietist

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life, including a social concern for ...

s, rationalists, and conservatives. Historian Thomas S. Kidd argues that after 1689 and the success of the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

,

: " ew Englanders'religious and political agenda had so fundamentally changed that it doesn't make sense to call them Puritans any longer."

Denominations that are directly descended from the Puritan churches of New England include the Congregationalist Churches, a branch of the wider Reformed tradition: the United Church of Christ

The United Church of Christ (UCC) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination based in the United States, with historical and confessional roots in the Congregational, Calvinist, Lutheran, and Anabaptist traditions, and with approximatel ...

, the National Association of Congregational Christian Churches

The National Association of Congregational Christian Churches (NACCC) is an association of about 400 churches providing fellowship for and services to churches from the Congregational tradition. The Association maintains its national office in Oak ...

, and the Conservative Congregational Christian Conference.

See also

*Pine tree shilling

The pine tree shilling was a type of coin minted and circulated in the thirteen colonies.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony established a mint in Boston in 1652. John Hull was Treasurer and mintmaster; Hull's partner at the "Hull Mint" was Robert S ...

Notes

References

Bibliography